Datasets and data science for complex molecular reactivity

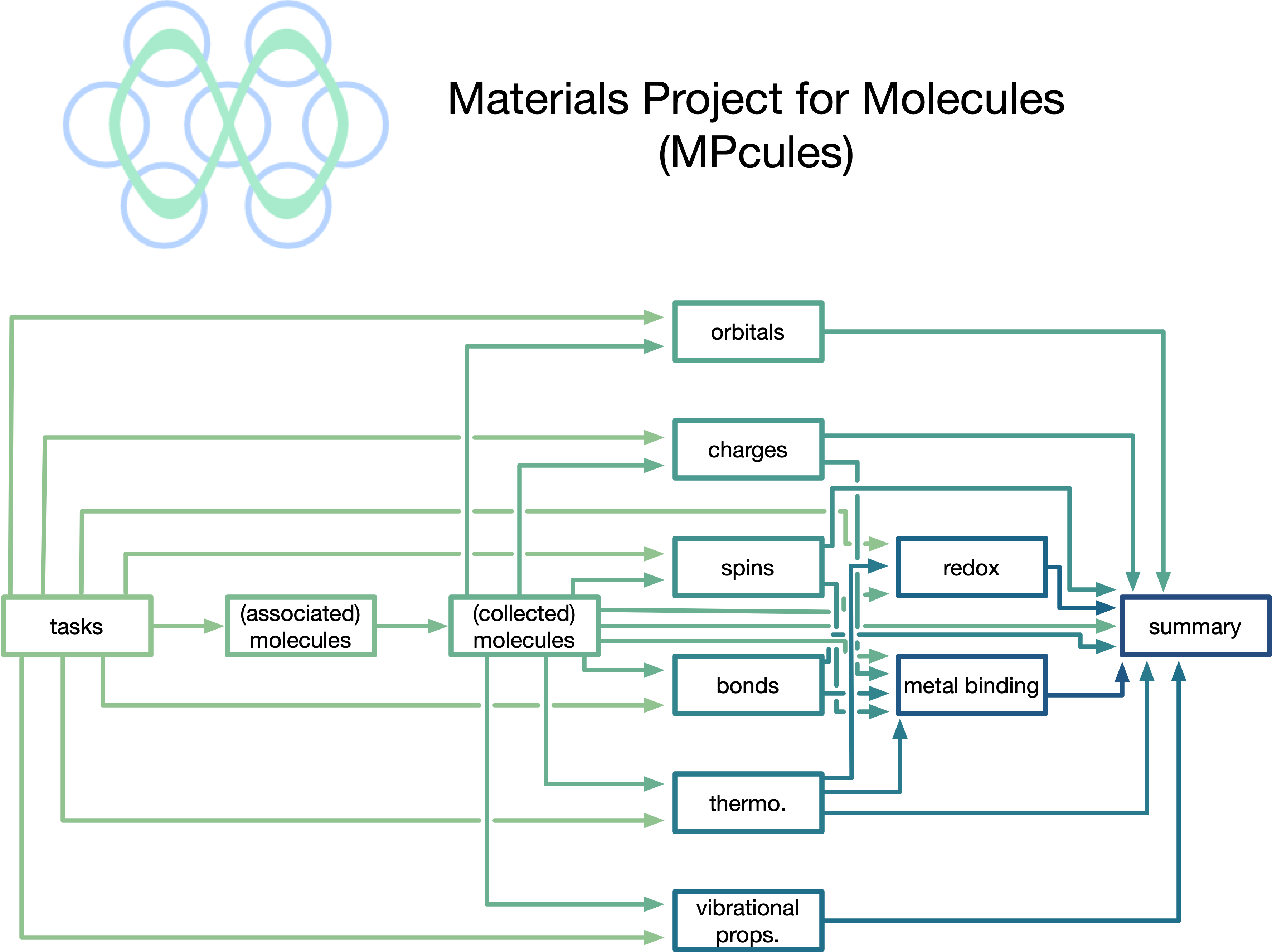

High-throughput density functional theory (DFT) studies of molecules have traditionally been limited to relatively stable species - neutral, closed-shell, and often in the gas phase. However, reaction cascades in domains like electrochemistry often involve radical, charged, and metal-coordinated species in a solvent environment. To facilitate studies of such complex and reactive systems, I have developed methods to automate calculations of reactive ground-state molecules as well as reaction energy barriers (based on transition-state theory and Marcus theory), allowing for the accurate prediction of reaction thermodynamics and kinetics from first-principles.Using the workflows that I have devised and implemented, I have generated large open datasets containing the properties of reactive molecules. Much of the data that I have generated is accessible on the Materials Project, making it accessible to computational experts and novices alike!

In addition to providing data as a community resource, I and my colleagues use computational datasets to study reactivity (see below). The data that I generate is also used within my research group and elsewhere to train machine learning models.

The eventual goal of this work is to be able to quickly and accurately predict the properties of arbitrary molecules and reactions throughout chemistry and electrochemistry with DFT-level accuracy (or better).

A new approach to exploring reactivity

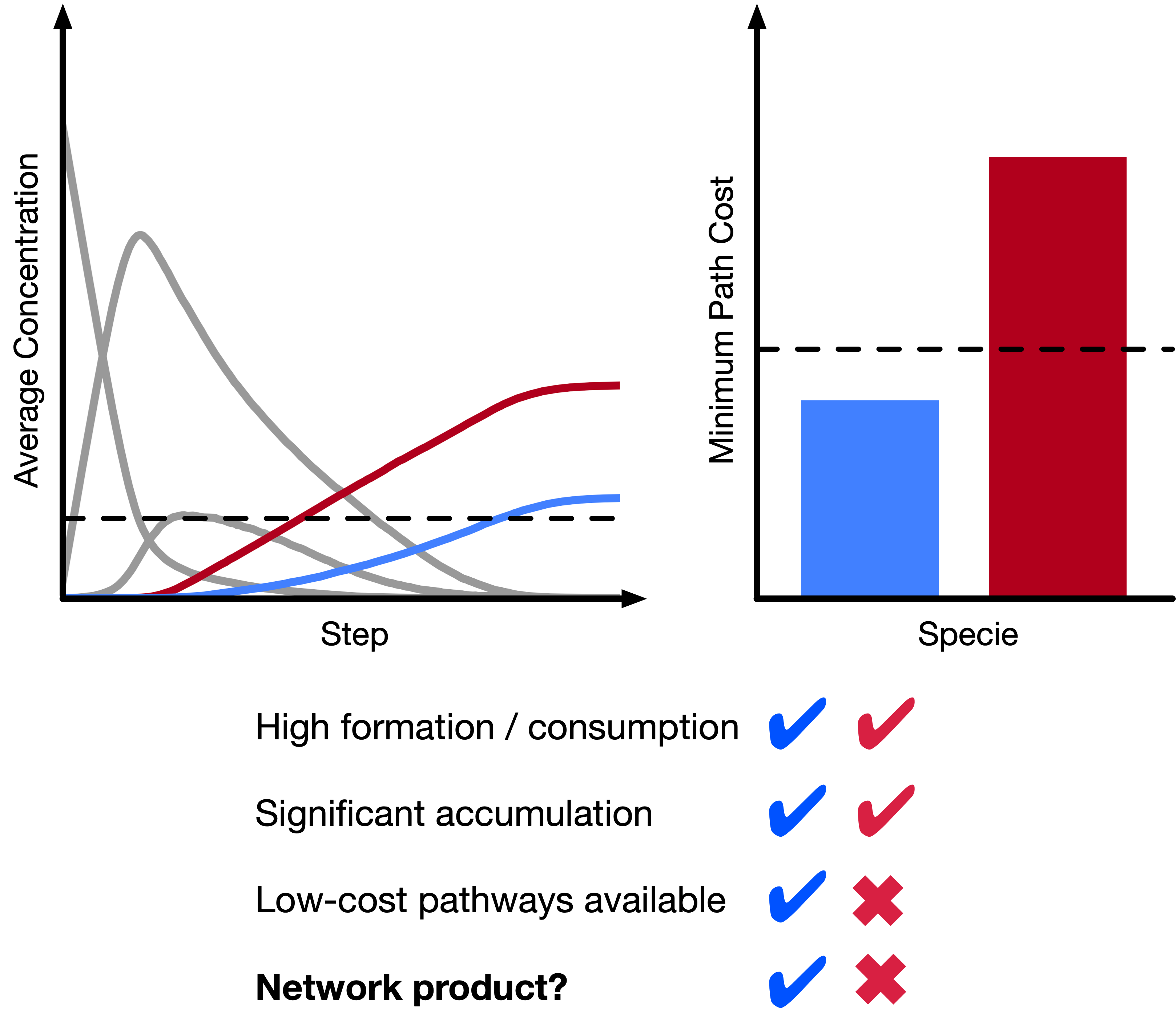

Understanding and controlling reactivity is key to a range of technological applications, from manufacturing to transportation and electronics. Typical theoretical studies of reactions involve low-throughput molecular simulations, using some combination of DFT and reactive or ab initio molecular dynamics. Recently, there has been growing interest in chemical reaction networks (CRNs), which abstract away the complexity of the quantum chemical potential energy surface, allowing for efficient exploration of even very complex reactive spaces.However, CRNs have not been applied to study electrochemistry until very recently. In part, this is because electrochemical reaction mechanisms are not well understood, making methods based on chemical intuition or reaction templates intractable. My colleagues and I develop new methods for constructing and analyzing (electro)chemical CRNs, with the goal of automatically revealing the inner workings of complex chemical processes without prior domain knowledge and without relying heavily on chemical intuition. Most recently, we have developed tools to generate CRNs based on filters and stochastic methods to not only identify pathways to known species of interest but also automatically identify the natural products of CRNs using simple heuristics. With this method, it is now possible to easily and rapidly generate hypotheses for experimental characterization and in-depth mechanistic studies of complex reactive processes (such as those in Li-ion batteries) using only computed reaction thermodynamics.

As part of ongoing collaborations with the Blau Group at LBNL, I continue to build on the successes of these methods and devise new ways to efficiently explore reactive spaces.

Revealing the mechanistic origins of electrolyte degradation

Electrolyte reactivity is one of the major drivers of inefficiency and capacity loss in metal-ion batteries. When uncontrolled, electrolytes can electrochemically react to form gases (which can cause swelling and explosions) or lower the cell lithium inventory. On the other hand, high-performance electrolytes selectively react to form passivation films, called interphases. It is therefore essential to understand how current electrolytes react and predict how electrolyte additves and next-generation components might affect reactivity.Using DFT, I construct elementary reaction mechanisms to understand possible degradation pathways. For instance, a community college intern and I examined the behavior of lithium hexafluorophosphate (LiPF6), the most common salt used in Li-ion batteries today. We found that the oft-cited hydrolysis mechanism is thermodynamically and kinetically unfavorable at room temperature, while LiPF6 can rapidly react with Lewis bases like lithium carbonate (Li2CO3)!

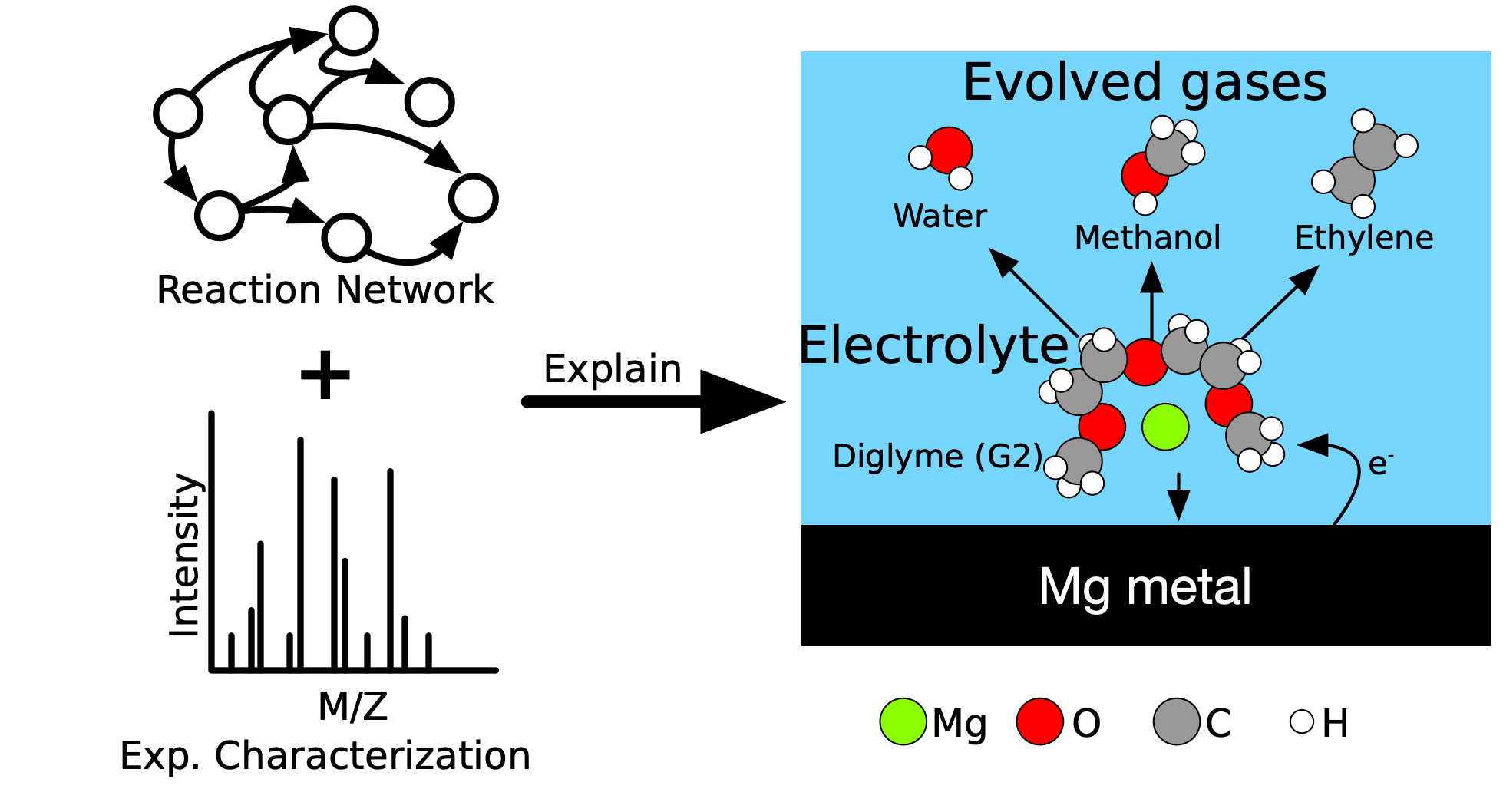

CRNs can help to understand electrolyte degradation, exploring more broadly and more thoroughly. I recently demonstrated the power of CRNs and DFT to explain electrolyte degradation in Mg-ion batteries. With no prior knowledge of gaseous or organic decomposition products, I was able to predict what gases would evolve during Mg plating (in agreement with experimental spectra) and indicate how the observed gases out-competed other possible products.

Multiscale modeling of energy technologies

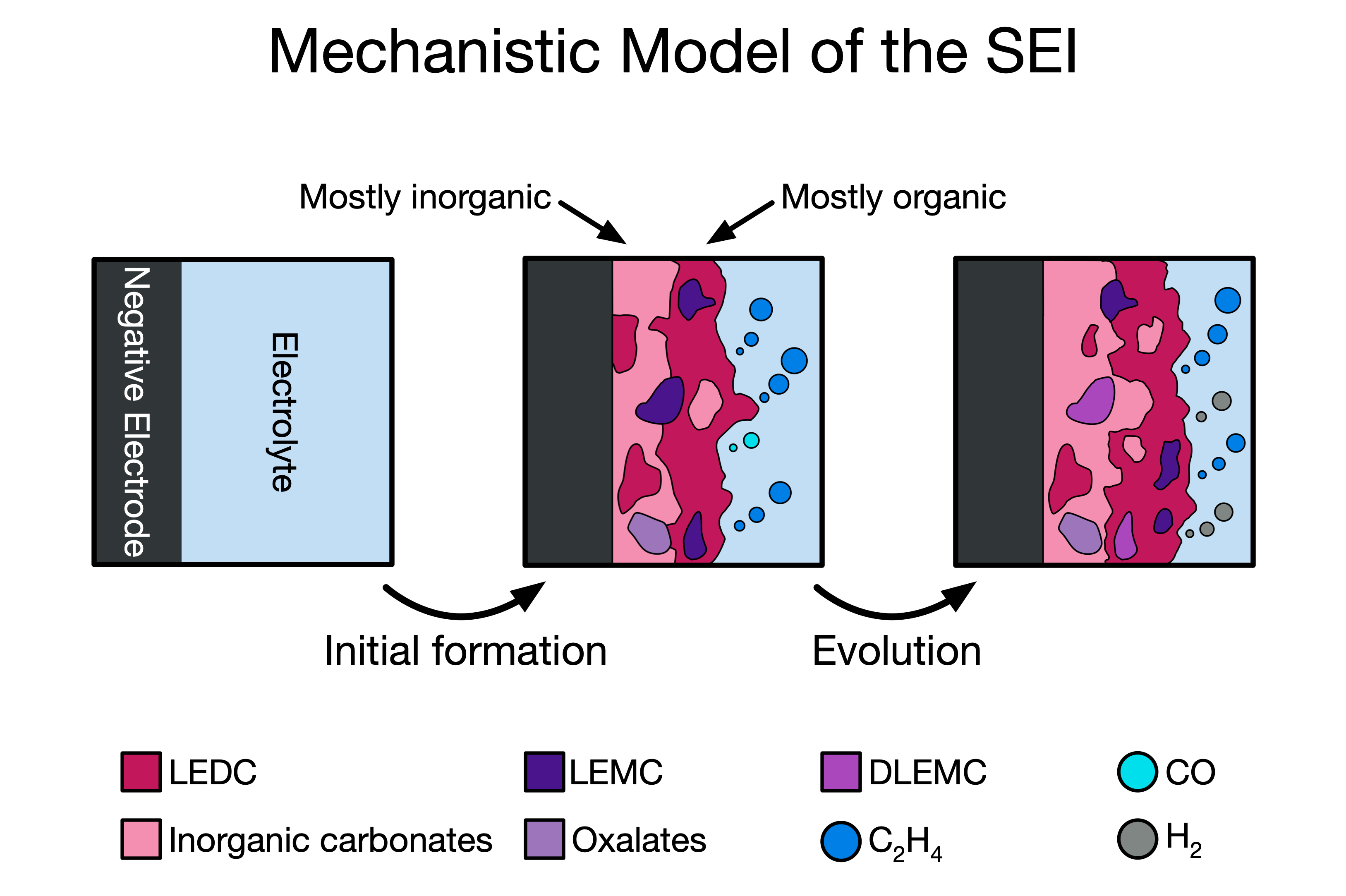

Interphases, which form as a result of electrolyte decomposition in metal-ion batteries, are critically important for allowing reversible cycling and preserving battery capacity. However, they are also notoriously difficult to study. In part, this is because of the disparate time scales involved in interphase formation. Individual reactions occur in picoseconds, while the interphase continues to grow and evolve for hundreds or even thousands of hours.Multiscale modeling provides an opportunity to access long time scales while retaining the accuracy of atomistic methods. I and my colleagues use a variety of multiscale techniques to analyze battery interphases. Combining reaction mechanisms from CRN analysis in a microkinetic simulation, I was able to trace the mechanistic origins of the bilayer interphase structure on the negative electrode of Li-ion batteries and moreover identify how different interphase components might electrochemically degrade over time. In a collaboration with researchers at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, I helped to develop a continuum-scale model of interphase growth that includes dozens of elementary mechanisms from DFT. This model, the most complex of its kind ever produced, can easily simulate thousands of hours of electrochemical cycling or voltage holds, revealing interphase growth dynamics and gas evolution behavior while also connecting directly to device-level experimental observables like parasitic current.

I am excited to continue pushing the envelope on multiscale modeling in energy storage, leveraging atomistic simulations in device-level models considering both electrodes and accurate (thermal, mass, and charge) transport.